In 1494 the ‘Treaty of Tordesillas’ divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly between Spain and Portugal along a North-South meridian 370 leagues (1770 km) west of the Cape Verde (off the west coast of Africa), roughly 46° 37' W. Very little of the newly divided area had actually been seen, as it was divided according to the treaty. The West (i.e. the newly discovered ‘Americas’) therefore belonged to Spain, while the countries east of Cape Verde belonged to the Portuguese sphere. Although both countries agreed that the line should be considered to be running around the globe, dividing the world into two equal halves, it was not clear where the line should be drawn on the other side of the world because longitude could not be determined accurately in 1494. Moreover, the church and many others still believed the Earth to be flat. The line was not strictly enforced — the Spanish did not resist the Portuguese expansion of Brazil across the meridian. The world was just too huge for these European nations.

Seeing the world from the other side of the globe it needs to be mentioned that the Moluccas (i.e. the fabled Spice Islands) were reached and claimed by Portugal in 1512/13. The Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan and his principal cosmographer Ruy Faleiro, spurned by the Portuguese king but backed by the Spanish king, thought that they were within the Spanish half of the world. When Magellan reached and claimed for Spain the Philippines in 1521, he confirmed that the Moluccas were within the Spanish half. After his death in the Philippines, two of his ships did reach the Moluccas. Thus both countries now claimed the Moluccas, creating a new dispute.

In 1529 the ‘Treaty of Zaragoza’, more precisely specified the so-called ‘anti-meridian’. This treaty specified that the pole-to-pole line of demarcation near Asia should pass 297.5 leagues (or 17°) to the East of the Moluccas, which places the Zaragossa line near 145° East longitude. The treaty states that this line passes through the islands of Las Velas and Santo Thome, named Islas de los Ladrones (Islands of Thieves) by Magellan, which are now called Guam and the Mariana Islands. These islands were further specified as lying 19° northeast by east of the Moluccas, more or less.

Portugal gained control of all lands and seas west of the line, including all of Asia and its neighboring islands so far 'discovered', leaving Spain most of the Pacific Ocean. Spain agreed to relinquish all claims to the Moluccas upon the payment of 350,000 ducats of gold by Portugal. Although the Philippines were not named in the treaty, Spain implicitly relinquished any claim to them because they were well west of the line. Nevertheless, by 1542, King Charles V decided to conquer them, judging that Portugal would not protest too vigorously because they had no spice, but he failed. In 1565 King Philip II succeeded and claimed the Philippines for Spain.

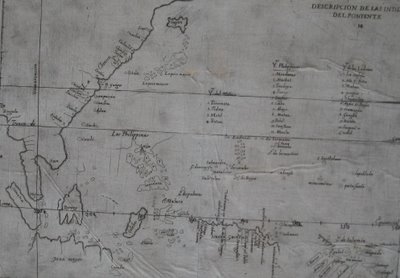

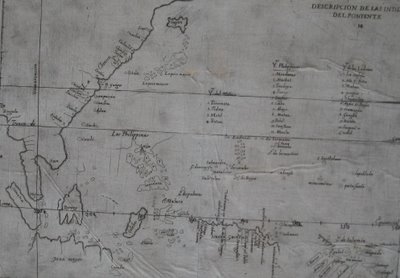

This political map (full of errors) from 1601 covers Southeast Asia and is based on the manuscript charts of Juan Lopez de Valasco produced around 1575. Shortly afterwards, between 1580 and 1640 Spain dominated Portugal as can be seen in this map that offers a great interpretation of the ‘Treaty of Zaragoza’. The map fixes the Line of Demarcation between the Portuguese and Spanish spheres of influence well to Spain’s advantage and grants Spain the famed Spice Islands (Moluccas). Originally the Line of Demarcation should have been East of the Moluccas which would have meant no Spanish Philippines.

According to Thomas Suárez in his ‘Early Mapping of Southeast Asia’ (from 1999), the list of islands in the 1575 Valasco chart established the modern name ‘Philippines’ for the entire archipelago.

The map was printed in Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas ‘Historia General de los Castellanos en las Islas i Tierra Firme del Mar Océano’ from 1601.

Labels: history, Philippines